Vitamin D: Key to Bones, Immune System and Wellbeing

17.10.2025

Are there mirrors that are too high?

Recent studies show that too high a vitamin D level can be just as harmful as one that is too low. In general, an optimal vitamin D level is between 50 and 80 ng/ml. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with immune deficiency. High levels of vitamin D can suppress the immune system, which can be beneficial in the short term when it comes to autoimmune diseases or aggressive inflammatory diseases. However, if an infection is the cause of a disease, vitamin D levels should be more moderate so that the immune system can fight the infection. We should remember at this point that vitamin D is a steroid.

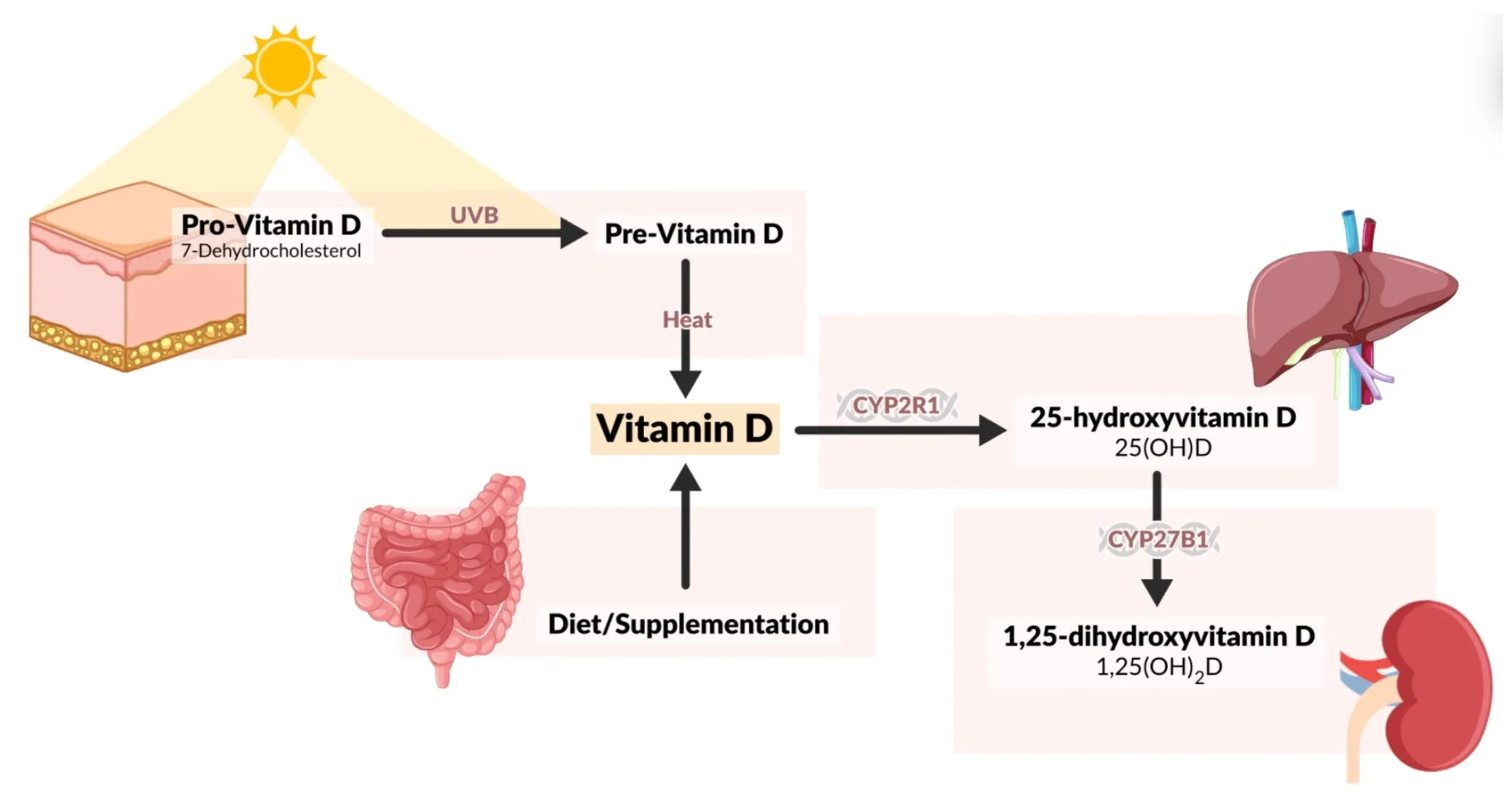

What is vitamin D?

Vitamin D, actually a prohormone, is stored in the body, in the liver and in adipose tissue. It plays a central role in calcium and phosphate metabolism and is involved in processes such as blood pressure regulation, immune function and cell growth. Deficiency is associated with diseases such as rickets, osteoporosis, multiple sclerosis, and cancer (Holick, 2007).

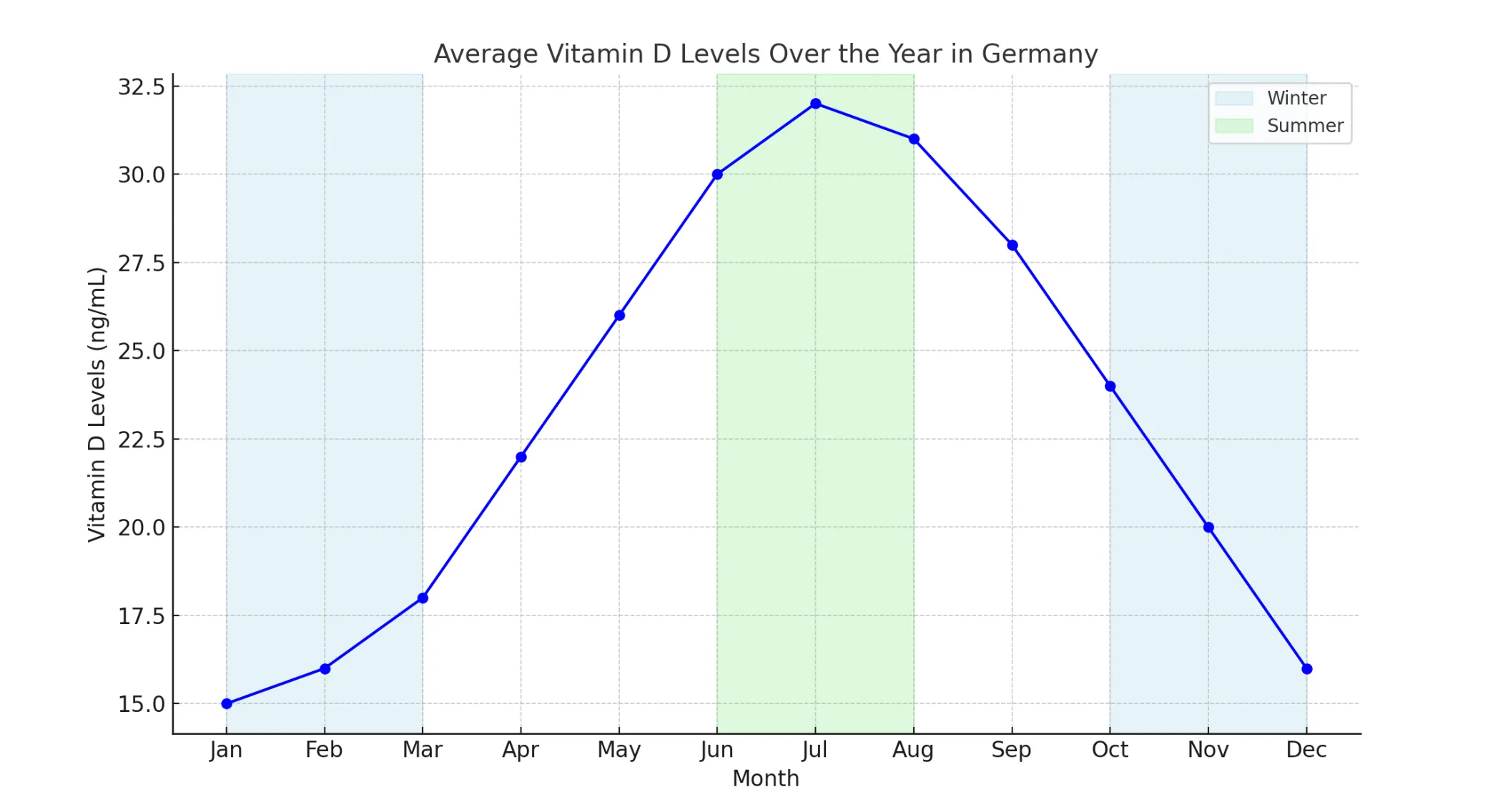

The sharp seasonal fluctuations in vitamin D levels contribute to an increase in our vulnerability to infections, particularly during the winter months when vitamin D levels are at their lowest. The connection between low levels and the winter flu epidemic is well established (Sabetta et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2007). Sabetta et al. (2010) showed that a vitamin D level of over 38 ng/ml offers significantly better protection against infections.

Limits and effects

Health conditions that have been linked to vitamin D levels based on various studies are listed below.

Natural mirrors

Our focus on natural vitamin D levels is based on studies that have examined indigenous populations in equatorial regions. This research shows that traditional peoples such as the Maasai and Hadzabe in East Africa have average 25 (OH) D levels of around 46 ng/ml (115 nmol/l), which can be regarded as evolutionarily “normal” levels. These levels are achieved through regular but not excessive exposure to the sun, suggesting that they could serve as natural targets for humans (Luxwolda et al., 2012).

upper limits

To fully understand this topic, it is important to know that vitamin D toxicity is extremely rare and would have to be caused almost intentionally. With regular blood tests, the risk is virtually eliminated. Instead, the real concern should be the widespread vitamin D deficiency that we face in Europe. This is impressively illustrated by the title of a systematic review published in 2016: “Vitamin D deficiency in Europe. pandemic”? The authors summarize: “Vitamin D deficiency is widespread across the European population, with worrying prevalence rates that require action from a health policy perspective” (Cashman et al., 2016).

Can you overdose on vitamin D?

One way to completely rule out toxicity is to use a blood analysis. Here, the vitamin D storage value 25-OH vitamin D is preferred, as we do in our analyses. Other vitamin D markers are only relevant if you're looking for very specific information. If we look at the studies on this blood value, the following picture emerges: A retrospective cohort study by the Mayo Clinic (Dudenkov et al., 2015) shows that vitamin D toxicity is extremely rare. When evaluating over 20,000 measurements over a period of 10 years, only 1% of people had values above 100 ng/ml, and only one case of acute toxicity was found at 364 ng/ml. This case was caused by taking 50,000 IU daily for several months. There was no evidence of hypercalcaemia in people with levels above 50 ng/ml, showing that even slightly elevated levels are safe.

The results confirm that vitamin D toxicity usually only occurs as a result of extremely high and long-lasting dosages of dietary supplements (Dudenkov et al., 2015). According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), vitamin D toxicity usually occurs at serum 25 (OH) levels well above 150 ng/ml. This toxicity is primarily expressed by hypercalcaemia, which can result in symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness and, in extreme cases, kidney failure and soft-tissue calcification. However, such high levels are achieved almost exclusively through excessive intake of vitamin D supplements, often at doses well in excess of 10,000 IU daily. Sun exposure alone does not cause toxicity because excess vitamin D is converted into inactive forms in the body (NIH, 2020). This data shows that regular blood tests are a safe way to monitor vitamin D levels and prevent toxicity.

Conclusion — Why your vitamin D level is crucial

In summary, an adequate vitamin D level is essential for numerous health processes. From bone health to the immune system to the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases — vitamin D plays a key role in many biological processes.

Current scientific findings show that natural vitamin D levels, such as those found in traditional population groups in sunny regions, are often significantly higher than the usual levels in modern society. Deficiency may be associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, infections, and cognitive impairment.

But it's not just a matter of having enough vitamin D — Values that are too high can also be problematic. Vitamin D levels that are too low can significantly reduce the quality of life, but an overdose can also have adverse effects. That's why it's important to keep your own vitamin D levels To be checked regularly. Especially after starting vitamin D supplementation, a new measurement should be carried out after 2-3 months to ensure that the levels remain within the optimal range.

Vitamin D also influences the metabolism of other important nutrients. For example, an increased vitamin D level can increase the need for magnesium and calcium. In addition to vitamin D levels, it may therefore be useful to check values such as calcium (in blood or urine), magnesium in erythrocytes and parathyroid hormones. These markers provide information on whether calcium metabolism is balanced and no adverse side effects occur.

By knowing and regularly checking your levels, you can actively contribute to your long-term health. Individually adjusted vitamin D levels not only support the immune system and bone health, but can also sustainably improve overall well-being and quality of life.

---

studies

Holick, M.F. (2007), “Vitamin D deficiency,” New England Journal of Medicine, 357 (3), pp. 266—281.

Dudenkov, D.V., Yawn, B.P., Oberhelman, S.S., Fischer, P.R., Singh, R.J., Cha, S.S., Maxson, J.A., Quigg, S.M., & Thacher, T.D. (2015). Changing Incidence of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Values Above 50 ng/mL: A 10-Year Population-Based Study. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 90(5), 577-586

Webb, A. R., Kline, L., Holick, M. F. (1988), “Influence of season and latitude on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3: exposure to winter sunlight in Boston and Edmonton will not promote vitamin D3 synthesis in human skin,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 67 (2), pp. 373-378.

Sabetta, J.R., DePetrillo, P., Cipriani, R.J., Smardin, J., Burns, L.A. & Landry, M.L. (2010), “Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and the incidence of acute viral respiratory tract infections in healthy adults,” PLOS ONE, vol. 5, no. 6, p. e11088.

Grant, W. B., Moan, J. & Reichrath, J. (2007), “Epidemic Influenza and Vitamin D”, Epidemiology & Infection, Vol. 135, no. 7, pp. 1095-1100.

Moretti, R., Morelli, M.E. & Caruso, P. (2018), “Vitamin D in Neurological Diseases: A Rationale for a Pathogenic Impact,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 19, no. 8, p. 2245.

Sailike, B., Onzhanova, Z., Akbay, B., Tokay, T. & Molnár, F. (2024), “Vitamin D in Central Nervous System: Implications for Neurological Disorders,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 25, no. 14, p. 7809.

BMC Neurology (2020), “Vitamin D and the Risk of Dementia: A Meta-Analysis,” BMC Neurology.

Littlejohns, T.J., Henley, W.E., Lang, I.A., Annweiler, C., Beauchet, O., Chaves, P.H.M., Fried, L.P. & Llewellyn, D.J. (2014), “Vitamin D and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease,” Neurology, vol. 83, no.

Chapuy, M.C., Preziosi, P., Maamer, M., Arnaud, S., Galan, P., Hercberg, S. & Meunier, P. J. (1997), “Prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in an adult normal population,” Osteoporosis International, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 439-443.

Dawson-Hughes, B. (2013), “What is the optimal dietary intake of vitamin D for reducing fracture risk?” , Calcified Tissue International, vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 184-190.

Luxwolda, M.F., Kuipers, R.S., Kema, I.P., Dijck-Brouwer, D.A. & Muskiet, F.A. (2012), “Vitamin D status indicators in indigenous populations in East Africa,” British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 108, no. 9, pp. 1557-1561.

Borsche, L., Glauner, B. & von Mendel, J. (2021), “COVID-19 Mortality Risk Correlates Inversely with Vitamin D3 Status, and a Mortality Rate Close to Zero Could Theoretically Be Achieved at 50 ng/mL 25 (OH) D3: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” MDPI Nutrients, Vol. 13, no. 10.

Benskin, L.L. (2020), “A Basic Review of the Preliminary Evidence That COVID-19 Risk and Severity Is Increased in Vitamin D Deficiency,” Frontiers in Public Health, September 10, Vol. 8, p. 513. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00513.

Hastie, C. E. et al. (2022), “Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank,” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 107, no. 5, pp. 1484—1502. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab892.

Entrenas Castillo, M. et al. (2020), “Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among hospitalized patients for COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical study,” Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, vol. 203, p. 105751. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105751.

National Institutes of Health (NIH), “Vitamin D — Health Professional Fact Sheet,” Office of Dietary Supplements, 2020.

Pludowski, P., Grant, W.B., Karras, S.N., Zittermann, A., & Pilz, S. (2024). Vitamin D Supplementation: A Review of the Evidence Arguing for a Daily Dose of 2000 International Units (50 mcg) of Vitamin D for Adults in the General Population. Nutrients, 16 (3), 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16030391

Peterson, A. L., Mancini, M., Horak, F. B., et al. (2021), “A randomized, controlled pilot study of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on balance in Parkinson's disease: Does age matter?” PLOS ONE, 16 (5): e0251097.

Frontiers in Neurology Review:

Peterson, A. L., McAuley, A., et al. (2021), “A Review of the Relationship Between Vitamin D and Parkinson Disease Symptoms,” Frontiers in Neurology, Vol. 12, p. 645631.

About the author

Ruth Biallowons

CMO & Co-Founder

Ruth Biallowons is a board-certified general practitioner with a specialization in Functional Medicine and over 18 years of clinical experience in treating complex chronic conditions. She supports individuals with autoimmune diseases, fatigue syndromes, and hormonal imbalances in restoring their health through a holistic approach. Currently, she is building aescolab as Co-Founder and Chief Medical Officer—a start-up focused on comprehensive lab diagnostics and personalized lifestyle intervention recommendations. She also leads Biallomed, one of Germany’s leading private practices, specializing in functional diagnostics, micronutrient medicine, and individualized treatment strategies. In addition, she hosts her own podcast and is a sought-after speaker at conferences, podcasts, and medical events, where she educates both health-conscious individuals and healthcare professionals on a wide range of medical topics. Her work combines deep medical expertise with a strong entrepreneurial vision to create modern, real-life health solutions. Ruth Biallowons studied medicine in Germany and has continuously expanded her education both nationally and internationally, including advanced training at Harvard Medical School Immunology) and in areas such as functional medicine, nutritional therapy, and integrative health promotion.

More interesting articles

Blood tests deciphered: Why not all analyses are the same

Omega-3: Why your body can't do without